When we left off, you, dear reader, had just finished making a list of qualities that you wanted to find in your substitute yarn. Now comes the fun part: yarn shopping.

Step 4: Shopping aroundBefore you skip joyfully down to your friendly neighborhood yarn shop, or begin clicking madly with your mouse, remind yourself of the parameters for your yarn search. Start by taking a look at the gauge notation(s) you made at the top of your lists. Remember how we talked about the recommended gauge for the specified yarn, and the gauge the designer used? If they are the same, skip to the next paragraph. If they are not the same, I hope that by now you've figured out why they differ, and you understand why you need to find a substitute yarn that knits at about the same gauge as the recommended gauge for the specified yarn.

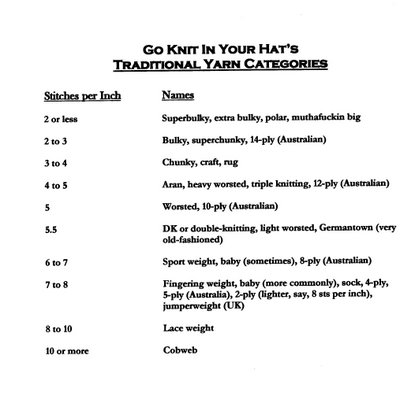

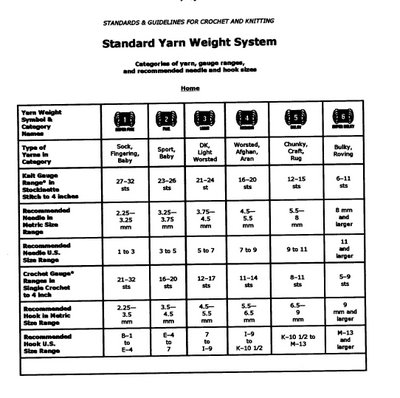

The starting point for your yarn search is that gauge notation. It will be expressed in a number of stitches to an inch.* This number allows you to make an apples-to-apples comparison while shopping (or as close you you can reasonably get, given how idiosyncratic yarns can be). When looking at yarns, you want to begin by narrowing down your choices to include only yarns that knit at this many stitches to the inch.

For example, suppose the pattern calls for Plymouth Galway wool. The recommended gauge for this yarn is about 5 sts to the inch, a straightforward worsted weight gauge. You must consider only yarns that knit comfortably at 5 sts per inch.

Go to wherever it is that you like to yarn shop; hopefully, this will involve a cool bricks-and-mortar shop like my beloved

Rosie's, but I understand that sometimes it isn't possible due to geography or other reasons. Wherever you begin your search, limit yourself to only yarns that knit comfortably at 5 sts per inch. You can ask a salesperson to show you the yarns or tell you which fit that criterion, or if you're internet shopping, you'll usually be able to search yarns by gauge.

To get back to my mythical example, if I were trying to find a substitute yarn for Plymouth Galway, I'd go into Rosie's and start looking at all the worsted weight yarns for sale. Here's a list of yarns you would find that knit comfortably at 5 sts per inch:

Cascade 220

Cascade 220 Superwash

Rowan Kid Classic

Berroco Suede

Classic Elite Bam Boo

Diarufuran

Creative Focus Cotton

Classic Elite Premiere

Katia Jamaica

Plymouth Encore

Cascade Pima/Tencel

Classic Elite Classic Silk

Reynolds Odyssey

There might be some more, but that's enough to get you started. You know that each of these yarns on the list can perform well at a 5 stitches to an inch gauge; now you need to work your way down, paying attention to the list of druthers you made. Must be machine washable? Then Cascade 220 Superwash, Plymouth Encore, Creative Focus Cotton are good choices. Allergic to wool? Then consider Bam Boo, Creative Focus Cotton, Classic Elite Premiere or Classic Silk, Cascade Pima/Tencel. Do you want a solid yarn? Rule out Odyssey (plies change color), Jamaica (self-striping) and Diarufuran (self-striping). Need good stitch definition? Consider Cascade 220, Classic Elite Premiere, Creative Focus Cotton, Plymouth Encore. Want something with a little bit of textural interest? Classic Silk has some nubbiness, Berroco Suede is sort of suede-y, Kid Classic has a slight halo from the mohair. Looking for drape? Premiere is probably your best bet, but the Bamboo and the Pima/Tencel might work. And so on.

You can see from my examples that all kinds of variables, including ones I didn't mention, like color choice, and cost (does anyone remember Cost Per Yard?) play into this, which is why it's a good idea to give yourself plenty of time at ye olde yarne shoppy -- leave the kids at home, and don't expect the non-knitting impatient significant other to be happy sitting around twiddling his/her thumbs while you debate which complements your coloring more: Wedgewood Blue or more of a teal? Once you've figured out some good possibilities, you will need to proceed to Step 4 and a half, below.

To continue my Plymouth Galway example, let's say I am going to make an aran-style sweater for my husband. I know right off the bat that I want wool or a wool blend; partly because I'm a purist and partly because I don't think I'd want to do a lot of stitch manipulation for cables unless I'm using a fiber with elasticity, like wool or a wool blend. That narrows me down to

Cascade 220

Cascade 220 Superwash

Rowan Kid Classic

Diarufuran

Plymouth Encore

Reynolds Odyssey

Because arans feature complex stitchwork and cabling, I'm going to nix the yarns that aren't solid colors. Bye-bye to Diarufuran and Odyssey (both of which I love, but just aren't right for this example). I'm going to exclude Encore merely because my husband hates acrylic. That leaves me with Cascade 220, Cascade 220 Superwash and Kid Classic. My first instinct is to eliminate Kid Classic because the mohair in it will create a sort of halo of fuzziness, and for all the work I'm going to be doing, knitting a man-size sweater with lots of patterning, I want the stitches and cables to pop. So I'm left with either Cascade 220 or Cascade 220 Superwash. From there, I'd balance out the convenience of superwash with the lower price of non-superwash. I'd probably also get my husband to take a look at the color card to see whether he particularly liked a color of either. And as a veteran yarn shop clerk, I can tell you that Cascade 220 -- whether superwash or not -- would be an excellent substitute for Galway in most situations. Certainly it would be one of my first recommendations as a substitute for Plymouth Galway.

Step 4 and a half: Buy one ball to swatch withYeah, yeah, I know, you don't wanna. Well, you should. If you're really looking for a good yarn substitution experience, especially if you're new to all this, you really ought to buy one ball of the proposed substitute and swatch it before you commit to it wholeheartedly. It can be hard to envision a stitch pattern in a different yarn and/or color, and some yarns that ought to work just plain don't. Sometimes yarns that are marked with a particular gauge don't end up working best at that gauge and need to be taken up or down a stitch per inch. Yarns -- like people -- have all kinds of quirks, and better to find out one ball in, then after you've bought a bunch of nonreturnable sales stuff from some Ebay seller.

Another advantage of doing a preliminary swatch is to give yourself a chance to go back and research the substitute yarn. Looking at a site like

Wiseneedle, which publishes unbiased reviews from knitters, can be tremendously valuable. Another place to check is

Knitter's Review; Clara reviews yarns, even subjecting them to wash and wear tests, and if you're lucky enough to find your proposed substitute reviewed there, you'll get some good information about it. Message boards (like the

forums of Knitter's Review or

Knitty's Coffeeshop) are other places where you can find out about knitters' real world experiences with particular yarns. Look for the appropriate thread or folder, and do a search first, to see if someone's already asked. If not, you can post a query and it's very likely knitters will respond to tell you their experiences. And one last, but potentially very valuable source for information, is your old friend Google: try Googling the name and manufacturer of the yarn to see what you get. If you scroll through your search results, you may get lucky and find that some crazy-ass blogger like myself has written a copious blog post about his or her experiences with this very yarn.

Meira Voirdire (if that's your real name), and Dorothy both have raised the question of why certain yarns that supposedly knit at the same gauge can vary substantially in the amount of yardage you get. For example, Yarn A allegedly knits at 5 sts per inch, and you get 100 yds. per 50-gram ball, and yarn B also allegedly knits at 5 sts per inch but you get 189 yds. per 50-gram ball. This would seem to not make sense, since there's a relationship between the amount of wool you get (weight) and yardage -- the more yardage in a ball, the thinner the yarn ought to be and therefore the tighter the stitches ought to be.

Meira and Dorothy, this is exactly why you need to prowl around a little on the Internet looking for yarn reviews. One explanation for the discrepancy -- raised by Queer Joe in a comment some weeks back (see, Joe; I do read your comments) -- is loft, or the amount of air that is wrapped up in a strand of yarn. Some yarns just have more loft: they are made in such a way that the fiber traps air within and plumps out the strand, making each stitch bigger than it would be relative to the amount of wool in it. These methods of construction can affect the weight to yardage ratio and mean that a ball of yarn goes farther because you're knitting more air into each stitch.

Sometimes it's as simple as the manufacturer screwing up and mislabeling the yarn. I saw a yarn advertised at an on-line seller whose name rhymes with Snit-Licks that claimed to knit at 7 sts per inch, but instead of getting 200 or so yards in 50g, you got 137; turns out there was a snafu of some sort and the label was wrong. It actually was more of a sport or DK weight. (They subsequently changed the website to reflect this.) Or maybe whoever tested the yarn for the manufacturer was having an off-day and miscalculated, or is a really loose or tight knitter.

I have to tell you that I've never before heard anyone say that manufacturers purposely mislabel their yarns, or that there's any kind of standard deviation, i.e., that you should always assume a yarn knits tighter or looser than the maker says it does. For whatever it's worth. (I, in fact, began as kind of a loose knitter, and originally had to compensate by going down two needles sizes from the recommended needle size. Since that time, I've tightened my gauge and now am spot-on with the recommended gauge about 97% of the time. But the other three percent of the time is a bitch, believe me.)

Whatever the cause, the only way to really know if a proposed substitute yarn is going to work well is to give it a whirl and swatch it. (And here is the biggest disadvantage to buying yarns on-line: you can't stop by and pick up one ball, swatch it, then stop by another day to buy more. You either have to put together a separate order along with your single ball, pay shipping for just a single ball or go out on a limb and buy a whole sweater's worth without having touched or felt or swatched the yarn.)

Step 5: Figuring out equivalentsWithout getting too carried away by this subtopic, once you've decided on a substitute yarn, you need to figure out how to purchase enough of it. And here comes a rule of thumb that will always stand you in good stead: BUY MORE THAN YOU THINK YOU NEED. There is nothing worse than running out of yarn before the end of the project, unless it's the creeping, sinking sensation you get as you are knitting along and begin to suspect that you will run out of yarn for a project, and keep trying to rationalize "hey, maybe I won't," but all along you know you really will, because you've used up 5 of the 10 balls just knitting the back, and it's a cardigan, so you know you'll need more to finish the front....

To figure out yardage, all you need is a calculator. Figure out how many balls of the specified yarn the pattern calls for (in my example, let's say 7 balls of Plymouth Galway) and how many yards are in each ball (Plymouth Galway runs about 210 yds. per ball), and you multiply them (1470 yds.). That's about how many yards you'll need to purchase.

Next, figure out how many yards are in a ball of the substitute yarn. Let's say Cascade 220, which, as the name suggests, has 220 yds. per ball. Divide the total number of yards you need (1470) by the number of yards in your substitute ball (220) and if the number doesn't divide evenly (hey, what are the chances of that happening?) round UP. In my example, 1470 divided by 220 is around 6.6 so I round up to 7. I need 7 hanks of Cascade 220. Being paranoid, I'd buy 8 and plan on returning the 8th if I don't use it. (Or more likely, I'd buy the 8th and not return it, using it for

Ship's Project hats or make mittens for my kids or something.) In my example, the original yarn and the substitute yarn ended up being close in yardage, so the number of skeins I had to buy ended up the same. If, for example, you chose to use, say, Reynolds Odyssey, the number would end up much different. Odyssey is put up in 104-yard skeins, so 1470 divided by 104 is something like 11.1, rounding up to 12; so I'd have to buy 11 or 12 balls of that to get the same yardage. Because the number of yards in a skein can differ so drastically from yarn to yarn, and because some yarns are sold in 50g balls while others are sold in 100g hanks, you can't assume that the number of skeins called for in the original yarn will work with the substitute. Check the math first.

I know some of you are going to say "Why are patterns often so off when it comes to yarn requirements?" I think every knitter's had an experience where s/he either ran tremendously short of yarn on a project, even though s/he bought exactly as much, or even a little more, than the pattern calls for; or the reverse, having 1 or 2 or more skeins leftover after a project is done. Here's another dirty little knitting secret: when designers write up a pattern, they usually only make 1 size of the pattern for a model, and they draft the rest of the sizes without actually knitting them. If you've made a size 36 sweater, you know how many skeins you used; but you've never made the size 42, and so you guess how many more skeins you think a knitter would need. Being a designer, your guess is an educated one, and the more you draft patterns, the better you get at it, but nevertheless, it is only a guess, and everybody guesses wrong sometimes.

If you're about to get all indignant and insist that designers knit every size of every pattern, well, I think you need to reality check. Designers don't get paid much for their work, especially considering all that goes into it, and often they have to supply yarn themselves for the model. Imagine how long it would take to make 4 or 5 sweaters instead of 1. Imagine how much it would cost to hire test knitters to knit 4 or 5 sweaters instead of 1. Imagine if you were only getting paid $100 for all that work. Just not realistic, I'm afraid.

But it's another good reason that it pays to round up. And if you purchase from a reputable bricks-and-mortar shop like

Rosie's, you will be able to return unused, pristine hanks for your money or after a longer time period, store credit, so save those receipts.

One last noteWithout sounding like a total bitch, I don't plan on becoming the Dear Abby of yarn substitution. The whole point of this exercise is for you to figure out how to do substitutions yourself. So please don't send me emails asking me if Yarn A is a good substitute for a pattern that calls for Yarn B. I won't answer such questions, telling you instead to "Wake up and smell the coffee!" or "Seek professional counseling immediately!"

*Readers using the Metric system, forgive my Americanocentrism. You, dear friends, can consider gauge over 10 cm (which is the same as Amurrican gauge over 4 inches).